LITERATURE REVIEW

In the CENF project an extensive literature review was conducted to give an overview of contemporary themes in adult numeracy (education )

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL LITERATURE REPORT

CLICK HERE FOR A LITERATURE REVIEW ON NUMERACY AND HEALTH

A NUMERATE SOCIETY & SKILLED WORKFORCE

There are innumerable reviews about numeracy (Coben, 2006b; Coben et al., 2003; Condelli, 2006; G. E. FitzSimons, 2004b; G. E. FitzSimons & Godden, 2000; Gal, 1993, 2000; Morton, McGuire, & Baynham, 2006; Tout & Gal, 2015), making almost impossible to cope with a shared consensual definition of what does it mean numeracy for everyone. This difficulty has been highlighted many times; hence we do not want to contribute with a new (and probably limited) review to the amount of previous works on that issue. Instead, the objective of this literature review done within the frame of CENF is to open up the floor for contesting the new challenges that numeracy must face in the near future, acknowledging all the previous work done in the field. Numeracy has been one of the main concerns for governments around the World since 1950s. We are living in a numerate society, full of codes, data, uncertainty, and people do need to use numeracy skills to deal with all of that. Numeracy is one of the most fundamental skills, baseline for higher cognitive processes, but still, indispensable. International organizations have devoted (and still devote) huge resources to define, update and assess numeracy. This report and CENF, as a project, may contribute to expand this work and move forward with it. Citizens with STEM skills, able to deal with societies challenges, opining opportunities for development, is a condition that all countries want for their own citizens. Governments want a skilled workforce. They ask for detailed studies about the type of numeracy skills embedded within employments. APEL policies were developed by the EU in the 1990s to cope with such requirements. Researchers have made visible the invisible. Numeracy is invisible to people (Diez-Palomar, 2019; Steen, 2001, Wedege, 2010). But it can be unpacked, tracked, and delivered to practitioners, decision-makers, teachers, to better train current and future learners. We need systematic reviews, to identify what are the key points, to pursue with our work in the field. The underlying report is a try to do it.

CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT OF NUMERACY

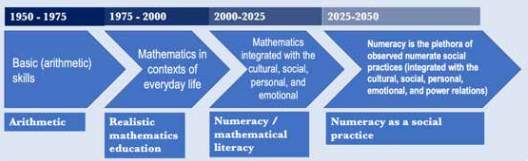

The concept of numeracy first appeared in the 1950s. Numeracy evolved from being associated to “basic arithmetic skills” towards a broader concept, referring to someone’s ability to interpreted data and make connections that allow him or her to understand business, science and technology. In 1982 Stringer claimed that being numerate means “having an ‘at-homeness’ with numbers” and “the ability to have some appreciation and understanding of information which is presented in mathematical terms” (Cockcroft Report, 1982, p. 11). In 1994, during plenary session of the first conference of the Adults Learning Mathematics organization (ALM), Withnall discussed five different concepts of numeracy (as mathematics, aptitude, functional numeracy, numeracy in everyday life, and as context-specific).

In the second phase of numeracy definitions, it was conceptualized as “mathematics in context, or mathematics in everyday life.” Different authors defined numeracy in realistic situations, bringing together components such as “making meaning about mathematics in real everyday settings”, “mathematics in context”, “everyday numeracy thinking”, etc. In 1997 Tout also contributed to the international discussion introducing another dimension to the concept: being numerate means being critical. Gal, van Groenestijn, Schmitt, Tout and Clermont created the ALL Numeracy Group. They operationalized the term “numeracy” and introduced for the first time the term “numerate behavior”, involving five complexity factors (complexity of mathematical information/data, type of operation/skill, expected number of operations, plausibility of distractors, and type of match / problem transparency).

In the 2000s the term numeracy evolved towards a more integrated concept with cultural, social, personal and emotional factors. Coben, O’Donoghue and FitzSimons (2000) published their Perspectives on Adults Learning Mathematics, an international handbook collecting the main contributions in ALM at that moment. In her chapter, FitzSimons organized her discussion concerning the adult learner of mathematics using a “macro- or institutional level” (including a social, cultural and political perspective), a “meso-or structural level”, and a “micro-or personal operational or subjective level.” Numeracy has been discussed in workplace contexts (nurses, cabinetmakers, farmers, warehouse pickers, etc.), in cultural settings, in social practices, etc. Current trends in defining numeracy suggest that it is a social practice (Yasukawa et al, 2018). Numeracy is historically and culturally situated.

DOMAINS OF NUMERACY

Drawing on the literature review conducted within the frame of the CENF (Common European Numeracy Framework) project, numeracy can be defined as a multifaceted term integrating eight different domains: learning and teaching, psychology factors, vulnerable groups, evaluation and assessment, theories and frameworks, professional development, contexts, and institutional support. Numeracy is about knowing, but also about doing. As stated by Coben, “To be numerate means to be competent, confident, and comfortable with one’s judgements on whether to use mathematics in a particular situation and if so, what mathematics to use, how to do it, what degree of accuracy is appropriate, and what the answer means in relation to the context.” From the learning and teaching point of view, there is a lack of literature on that issue, in the field of ALM.

Drawing on the psychological factors, adults have a complex affective relationship with numeracy. If we consider the perspective of the vulnerable groups, some studies have reported cases of migrants, ethnic minorities (Latina families, Roma people, etc.), other women, etc., whose numeracy skills have been undervalued.

From the evaluation and assessment standpoint, numeracy was taken as a serious thing by Governments all around the World. International surveys have tried to assess adults’ numerical competences (IALS, ALL, PIAAC), defining levels of competence.

A diversity of the theories and frameworks have been used to discuss about numeracy (sociocultural approach, Freirean studies, Realistic mathematics, Dialogic Learning, Critical Studies, Women studies), although since numeracy is usually defined as a social practice, the most frequent theoretical frame are the so-called socio-cultural theories.

In terms of “contexts”, there is a huge range of different contexts in which numeracy has been explored (e.g., laboratory and factory workers, in banking situations (transactions, etc.) but also in the supermarket, and diverse professions (e.g., nurses and carpenters, commercials, using ICT, numeracy at home-practices, etc.

However, drawing on a perspective in professional development, we noticed a lack of resources addressed to teach in service and pre-service teachers of ALM.

For the coming future it seems that numeracy faces a number of challenges. The literature review suggests that there are five main types of challenges: numeracy as a social process, the impact of ICTs on numeracy, critical citizenship, teacher and training programs, and assessment.